by Akis Gavriilidis

Published in International Journal of Science Culture and Sport (IntJSCS), December 2015 : 3(4)

ABSTRACT

From the late 80s – early 90s on, a new genocide was invented and started being talked about in Greece (and among the Greek diaspora): the «genocide of the Greeks of Pontus». This was accompanied by a more general revival of a particular ethnic Pontic identity.

This revival is often seen by many, including its protagonists, as one more variation of Greek nationalism and irredentism. However, in this paper I propose instead that we read these public identity performances as expressions of “anti-state nationalism”.

The Pontians manifest a particularity which, although presented as quintessentially and primordially Greek, in practice differentiates them from standard Modern Greekness. In my paper, I examine some examples of such manifestations in the field of legislative lobbying, establishment of public rituals, selecting names and nicknames for persons, places, institutions or football teams, translation activities, and political propaganda through typography and the cyberspace. I analyze these expressions of ponticity through the lens of political anthropology and philosophy and try to see to what extent these can be considered as an effort by the respective populations to escape the state, to become at least partly invisible to it and its bureaucracy.

Keywords: Pontians, language, translation, bandits, state evasion, performativity

From the late 80s – early 90s on, a new genocide was invented and started being talked about in Greece (and among the Greek diaspora): the «genocide of the Greeks of Asia Minor and the Pontus», allegedly commenced under the Ottoman Empire and completed by the Young Turks. This longer expression soon boiled down to «the Pontic genocide», as regards both the semantic and, importantly, the pragmatic level. After some years of lobbying and public rallies, its advocates had a bill voted at the Greek Parliament to the effect of «recognizing» this genocide and determining an official commemoration date for it.

As far as I know, this phenomenon did not very much capture the attention of the humanities; little –if anything at all- has been written about it from a theoretical perspective. The bulk of the relevant literature consists mainly in apologetic (pseudo-)historical texts or books, mostly in Greek or in (usually poor) English, aiming at documenting the genocide. This usually translates in adding and counting corpses, and presenting testimonies for their death, or photographs and maps depicting the activities of the flourishing Pontic community before its expulsion from Pontus. To a lesser extent, some articles have appeared in periodicals trying to distance themselves from the previous publications, and their cause, qualifying them nationalist and irredentist.

My approach, which I will try to expose in this article based on the results of a research I recently published in Greek (Gavriilidis 2014), is that the question is much more complex and interesting. Although this «neo-Pontic» discourse does adopt and make wide use of familiar motifs and patterns from the nationalist repertoire, it would be insufficient to just state that and close the discussion there. There is a totally new landscape for us to discover if we move from the descriptive to the performative dimension, and try to listen not (only) to what this discourse is stating, but also to what it does by stating it; not only to the words, but also to the things done with them. From this point of view, we would realise that, by using these patterns, the speakers/ writers are doing something different from, and arguably even contrary to, nationalism: they stage and publicly present a new kind of ethnic or quasi national identity, independent from –or not totally identical and subsumed to- Greek nationality.

I maintain that we can find here at work a kind of a performative contradiction, or of a différance in Derrida’s sense –in the sense of something that permanently postpones the closure of this discourse and makes it not fully identical to itself.

In what follows, I will provide evidence for this emergence of a different subjectivity through the performance of the genocide discourse and the relevant public rituals –or, better, through the development of a parallel, latent discourse within the first discourse (or beside, behind, below, on top of it). I will further discuss the possible explanations and political implications of this double –or multiple- function of this reference to the past.

A neo-Pontic movement

A first sign of the ambiguity of this campaign in favour of a «Pontic genocide» is to be found in the very term around which it was constructed, i.e. the term geno-cide itself – the «G-word», to borrow Mazower’s expression (2001).

It should be noted that this term was not mobilised in order to describe any newly discovered historical events; the fact that, during the violent clashes of the 1910s-20s in Anatolia, many people –among them Pontians as well, obviously- had lost their lives, was already known, but described with other terms until the late 1980s (such as i Katastrofí, o diôgmòs [the persecution] etc). The emergence of the “G-word” was a re-signification of these already known events, the attribution of a new signifier to existing signifieds.

Now why this signifier? First of all, this linguistic choice, while it seems to constitute yet another version of Greek nationalism (by drawing from the pool of its traditional anti-Turkish sentiment), could also be read as undermining it at another level. Because, if there is a specifically Pontic genocide, this implies that the Pontians are a standalone, separate genos –hence, possibly, not part of the Greek nation! It should be recalled here that the first component of this new signifier, the Greek term genos, especially in the 19th century had been widely used as a first handy translation for nation, before the introduction of ethnos which finally took over.

Let us also consider a strange effect produced by the date defined for the annual celebration of this «iméra mnìmis” [day of memory]. This was the 19th of May, after the date when Mustafa Kemal disembarked at Samsun and started his counterattack against the Greek invasion in Asia Minor –and, according to the legislators, his genocide. But this date, as is known to everybody (and certainly to the campaigners), is also a national holiday for the Turkish Republic, since its creation! Indeed, this was precisely the reason why it was chosen –i.e. with the conscious intention of bringing to the fore, and reminding everybody, the guilt and the responsibility of Turkey. As a performative gesture, (or, to be more precise, as a perlocutionary statement[1]), the choice was meant to convey the meaning: “what for you was a cause for joy and celebration, for us was a cause for sadness”. But the practical result of this decision is a situation of competitive identification between victim and victor, who now share the same «national» holiday. The imagined community of Pontians is now organised around a date which, whatever the intention, coincides with that of the Turks, and differs from that of the Greeks …

A politics of (re)naming

The same ambiguity, entrenched in the very conception and formulation of the genocide claim, pops up in every step towards a bolder affirmation of a public and more independent Pontic identity.

As examples of such bold but ambiguous affirmations, I will consider here two sets of activities, both of which, incidentally, have to do with language. The one is the peculiar toponymic “revival” of Pontus in the new places of settlement by the refugees in Greece, and especially in Northern Greece. Indeed, the refugees, in spite of their destitution and miserable condition, already during the 30s deployed a remarkable agency and autonomy: they not only tried –where and to the extent this was possible- to influence the selection of the concrete sites for their settlement, by privileging places geographically similar to their places of origin near the Black Sea, but they also exerted an interesting naming policy concerning these new villages (or new names for old villages). So today Greek Macedonia is full of toponyms consisting in the name of some town in Anatolia, preceded by the prefix “Nea, Neos” (New).

Also, to some extent, institutions were copied and transplanted from Pontus on to Macedonia, such as the monastery of Panaghìa Sumelà near Veroia, after another monastery with exactly the same name on the Pontic Alps, or the Frondistìrion Trapezoùndos, a high school in Kalamarià (a suburb of Thessaloniki built and peopled by the refugees who arrived after 1922) which borrowed the exact title of an older institution in Trebizond. Another is the football team of the same suburb, Apòllon, which, after having existed for decades under the name “Apòllon Kalamariàs”, in 2009 was renamed “Apòllon Pòntou” (about this linguistic policy, see more in Gavriilidis 2015a).

Lost in the original, added in translation

Another interesting manifestation of a desire for ethno-cultural autonomy was the translation of three albums from the Astérix comics series into what could be provisionally termed “the Pontic language” (Uderzo 2003).

From the outset, these publications present themselves to the prospective reader as a bizarre object defying traditional classifications. Even the translator credit is given in a very particular form, which points to no less than a different system of identification –not least in the administrative sense of the term. The translation is credited to “τη Σαββάντων ο Γέργον”, a syntagm which clearly cannot be the “real”, official name under which this person appears on the records of the Greek state. No such form is conceivable for naming a Greek citizen, as this naming will appear on his ID card: Greeks are permitted to identify themselves only by one Christian and one family name, (exceptionally by two), all of which must be in the singular. Furthermore, these names are expected to adhere to a very limited number of choices as regards their form; they may only use typified endings such as –is, –as, –os, or –ou. No articles can be used before, after, or between the first and the last name (except in oral speech).

Presumably, this person’s name as it appears on the registers of the Greek state must be something like Georgios Savvidis (or Savvantidis). Opting for this alternative designation, which violates almost all of the existing rules, points to a desire for a different way of marking identity and, even, kinship (“τη Σαββάντων”, a plural genitive case, denotes the familial origin of the person, meaning “of [coming from] the –s”, in the same way as the French “des –s”, the German “von” or the Dutch “van [den]” –all of which imply aristocratic ancestry, by the way).

The Pontian Astérix publications are accompanied by an 8-page long leaflet, which thematises precisely the question of the idiom used in them, its status, and the way it should be construed by the reader. Very interestingly, this leaflet was not printed as part of the album itself, probably due to international property rights and obligations for uniformity imposed on the production of any new Astérix linguistic version. It forms a separate (semi-autonomous) body, a nomadic/ parasitic prosthesis on the main body of the book, with a rather amateurish look, in different fonts, paper type and dimensions, which presumably was manually inserted into each copy of the album before distribution.

This leaflet is entitled “Pondiakì glôssa” [Pontic language], but the very first phrase of the text reads: “Pontic is a dialect of the Greek language …” (my italics). Thus, already from the beginning, in terms of both content and form, the reader is introduced to this oscillation, this dual status of ponticity, which seems to be at the same time inside and outside, self-standing and included, part and whole[2].

After this ambiguous presentation, which includes concise historical information about how Pontians have throughout the centuries been quintessential Greek and resisted to barbaric Eastern invasions, the leaflet goes on to provide the reader a short Pontic-Greek dictionary as well, which is presented as a “glossary”.

The decision to produce these translations did not correspond to any informational or communicational need. According to a traditional conception of the activity in question, a translation is made in order to give to a linguistic community access to texts from which they would otherwise be excluded, as these were not previously available in any language comprehensible to that community (Sakai 2006 & 2013). However, no such community –or individual- exists in this particular case; all three of the Astérix albums had already been translated to (standard) Modern Greek –as had any other album of the series, for that matter. Any person alive who can understand Pontic, can understand Modern Greek as well, or even better[3]; so if they wanted to have access to the content of the albums, they could consult these existing translations.

Accordingly, the decision to produce an additional translation into Pontic was a sheer act of the signifier, an effort to affirm the autonomy of this language and “put it on the map” as different from, and equal to, other languages –including Greek[4].

Romans like us

Speaking of maps, it is useful to note yet another formal detail of this publication. Everybody who is familiar with this comic series must have seen on its first page a standard depiction of, precisely, a map representing the area known today as France, with some genuine or imaginary Latin toponyms marked on it.

This map is quite telling by itself as it reveals one of the reasons why this specific comic series was preferred for translation: this is a narrative about a small community living near the sea at the north coast of a vast and powerful empire, encircled by but resisting to it, militarily and culturally, sticking to their own particular identity. Therefore, it could be seen as a strong pole of identification for the Pontians. Besides, given that the Astérix stories themselves are already based on purposefully anachronistic jokes and parallels with modern situations, they can serve as a vehicle for anybody willing to make their own political comments for today.

In this sense, precisely, it is important to note a point where the Pontic version diverges from the standard. As is also known, the first page map is accompanied by an equally standardized text in a frame at the bottom of the page intended to familiarise the reader with the setting and historical background of the narration that will follow. So, this text informs us that “We are in 50 BC. All of the then known world is conquered by the Romans” … and so on. But in the Pontic version, right here, after the word “Romans”, a small phrase in parenthesis is inserted, which does not appear in the original –nor in any other translation. This phrase reads:

όχι τ’ εμετέρ, αλλά εκείν α σην Ρώμην τη Ιταλίας.

Which translates literally as “not those of our own, but the ones from Rome in Italy”.

Indeed, the generic term that these populations used –if any at all- to describe themselves while in the Euxinus Pontus was not Πόντιος (no such collective identity had been created before the late 19th century), but Ρωμαίος =member of the Rum millet, former subject of the [Eastern] Roman Empire. In other Greek dialects, and in standard Modern Greek, this term had long ago been transformed to Ρωμιός, but in the Pontic language/ dialect it has not undergone this linguistic change, so the version still used in it absolutely coincides with the term describing the inhabitants of Rome, Italy!

The initiative to add this impressive joke constitutes a very unusual arbitrary intervention at the limits of translation ethics. But this intervention, if combined with the meaning of the gesture to “put on the map” the Pontic language and culture highlighted above, reveals a double and antithetic identification. The aspiring imagined community appears, as it were, to be organized around the following founding imagination: «We resisted the Romans/ We are the Romans»; we sympathize with a stateless tribe and, at the same time, with a highly organized, sophisticated and hierarchical empire.

The ghost of an aborted state

During the first two decades of the 20th century, apparently some efforts had been undertaken with the aim of creating a (more or less) Greek state at the Pontus.

This project is practically forgotten now; it certainly does not form part of the historical baggage of the Greek society at large, but it doesn’t seem to have figured very prominently in Pontic memory either; it has not been included in the oral, semi-private transmission through which all other elements of the Pontic ethnic identity were passed on transgenerationally.

During the «Pontic Enlightenment» of the past two decades, some mentions to it can be found in the relative paper and electronic publications. According to these, it seems that the project for such a state was promoted by some local elites, but also –if not mainly- from diasporic ones; a congress was held in Marseille, France, in 1917, initiated by a rich merchant with roots in Trebizond, with the aim to raise the issue before what we would call today «the international community» and start lobbying on this demand.

The dream of a Pontic state does not seem to have gained massive support with the population on the ground. Also, importantly, the Greek leader Elefthérios Venizélos, when asked to back the plan, clearly refused to do so, as he saw no realistic possibility of creating and sustaining such a state.

Not backed by anybody, the plan for a Pontic state was abandoned and defeated. After the victory of Kemal Atatürk and the expulsion of the Greek army and ethnic Greeks from Anatolia, it was practically never spoken about again –until recently when Internet zealots started making posts full of nostalgia about it. These include uploading images with the «flag» of Pontus and recordings with its «national anthem» (at least two different songs, though, are presented as such)[5].

In view of these manifestations, I think it is legitimate to formulate the following construction: this peculiar process of ethnogenesis, the tendency of the Pontians to conceive of and to present themselves as a separate génos, as a particular ethno-cultural identity, may be attributed to a nostalgia for this state –although this never existed, or maybe precisely for that.

This implied “secessionist” function could be accentuated if we take into account that, in the 20th century, the signifier in question, the «G-word», has been predominantly linked with two other peoples: the Jews and the Armenians. Both of these peoples were deemed by the international community as deserving to have their own nation-state after the recognition that they were victims of genocide.

As we know, in most cases the state is what creates the nation –by producing through its institutions cultural and linguistic homogenization, and generally speaking the feeling of a common belonging and solidarity between people who have never met each other and never will.

The desire for a separate nation-state, even if never fulfilled, had nevertheless emerged among the Pontians, unlike any other particular group among the descendants of the 1922 refugees. The latter have more or less indistinguishably mingled with the overall Greek population. To be sure, some of them try to keep the memory of their grandparents’ local provenance and the link with their compatriots: they form associations, organize trips to their former homelands, publish journals etc. However, this is only one –and usually not very crucial- dimension of their social existence. For those from the Black Sea, the capacity of being a Pontian often seems to be the primary source of their feelings of belonging, and of their duty for solidarity[6]. This can also explain why the commemoration date, from very early on, was monopolized by the Pontians, and today everybody refers to the event as «the day of the Pontian genocide», dropping the rest of the phrase about the «Asia Minor Greeks»[7].

In this particular case, we have the unusual phenomenon that such a process of homogenization was first set in motion, then violently arrested. Both of these aspects of the development, the appearance of the idea of a Pontic nation-state as well as its suppression, or better their combination, is what accounts for the resistance of «Pontism» to being totally absorbed by Hellenism.

All these practices which seem to recreate a «virtual Pontus» in Macedonia can be seen as a new appearance of the aborted embryonic state, in the form of a ghost.

This is part of the reasons why I consider insufficient to stick to traditional labelling and classifications. In the received arsenal of political science and international relations, we have the term «irredentism». I think this term is inadequate for the «new ponticity», at least if taken in its usual meaning as the tendency of one nation, or sections within it, to invade another country and annex regions supposedly inhabited by their co-nationals. (Maybe not so inadequate, though, if taken in its etymological sense: lack of redemption fits quite well with a situation where one cannot get rid of a permanent obsession which is never spoken about as such or represented in the symbolic order).

Pontian anarchists, Vlach bandits, and trans-tribal solidarity

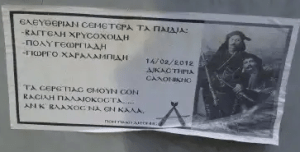

In the photograph reproduced below, we can see a very peculiar flyer which demands quite a long explanation before the reader can be said to have obtained some idea of its meaning(s).

As one can see, the flyer features itself a photo on the right. This is a photo of two armed men, dressed in (what today in Greece is recognized by everybody as) the traditional costume of Pontic guerrilla fighters who «took to the mountains» near the Black Sea in the early 20th century. (In Greek, the expression vgaìnô sto vounò [to go out on the mountain] has historically been used as a synonym for «to revolt, to become an outlaw». Hence, in Greek, as in several other languages in the Balkans and the Mediterranean, the metaphor used is the inverse of the English expression “to go underground”: here, one goes above ground, to the highlands. Besides, this is not really a metaphor; it corresponds to most historical experiences of revolts within living memory).

The text, on the top left, reads: «Freedom to ‘our own’ [emétera] kids», (the phrase is written in Pontic, but easily understandable by a standard Greek speaker), and then comes a list of three names, which are equally easily recognizable as typically Pontian names since they all feature the characteristic ending –idis (or –iadis).

These three persons were young anarchists who got arrested for their alleged participation in riots; the caption right next to the image informs the reader about the date and place determined for their trial, and implicitly calls for solidarity.

There is also a «postscript» in the brochure, which is equally, if not more interesting. The last paragraph reads:

«Our greetings to Vassìlis Palaiokôstas … Although he is a Vlach, we wish him well.»

The signature means «Pontic International», and is accompanied by the A for anarchism composed by the image of two kemantschés, the almost exclusive musical instrument used in the Pontic folk songs, and their bow.

The person to whom the flyers’ authors address their greetings, Vassìlis Palaiokôstas, was convicted in 2000 to 25 years of imprisonment for kidnapping and robbery, and sent to the high-security Korydallos penitentiary facility; in 2006 he escaped from there in a very spectacular way (with a meticulously organised helicopter flight). He got caught again, but escaped a second time in 2009 in the same way, together with an Albanian detainee; at the time or writing, he is still a fugitive.

His escapes, along with a «Robin Hood» reputation that has been created around him for allegedly distributing the gains from his crimes to poor families, earned him great popularity with the antiauthoritarian movement, and indeed for some while mainstream media were full of stories about Palaiokôstas’s contact and possible collaboration with anarchist activists whom he met while in prison.

I was not able to verify the claim made in this salutation, which I had never heard before (or after) from anywhere else, that Palaiokôstas is of Vlach ethnic origin. We know for a fact that he was born in Trikala, Thessaly, a city and a region where many Vlachs live.

But this is not that important. The really interesting question is why the author(s) should mention this at all, of all things, what is the desire that led them to bring up this capacity here or –even more- to imagine it, if it is not real.

In this connection, I find crucial that the Vlachs constitute one other big «minority/ majority» ethnic group within Greece, with a marked ethnolinguistic particularity as compared to standard Greekness. Their particular culture has of course no similarity whatsoever to the Pontian one as regards its content, but both groups are developing an almost identical «social poetics» (Herzfeld 2004) of liminal belonging. They both cling on their respective difference, but fiercely deny any allegation that this should exclude them from the Greek nation. On the contrary, they –at least their elites- both claim that their divergence from (modern) Greekness is a proof and a sign of a deeper conformity to an old, more genuine version of Hellenism, indeed its essence. The cliché phrase «we are more Greek than the Greeks» is common in both groups.

Importantly, one should bear in mind two additional features of the Vlachs: they speak a Latin-based language whose name, Aromanian, already by itself denotes its link to Rome –the same Italian city whose name is the basis for the self-appellation of the Pontians we came across before; and, also, they are considered as being the last nomad pastoralists on what is today Greek soil. The epithet «Vlàkhos» (in an older and longer version, oresìvios Vlàkhos = a mountain-dweller Vlach) is often used in a pejorative sense to mean «uncivilized person», somebody who is rude, unsophisticated, naive –but cunning at the same time («poniròs o Vlàkhos»).

In this sense, the «although» of the salutation phrase could equally be read as a «because»: we express solidarity to Palaiokôstas although he is not “teméteron”, not a Pontian like us, but a Vlach; but we do so because, being a Vlach, he is «sort of» like us: insubordinate, not conforming to the rules of hellenonormativity.

A “subversive, underground process”

I am not aware of any other presence of the self-proclaimed «Pontian Internationalists» in the public space, before or after this leaflet, and I am not quite sure whether this was serious or meant as some kind of parody or practical joke. But, whichever the case, even before Freud everybody knew that jokes are a quite serious affair and should not be dismissed as something of no importance. Jokes, notably, are the best way to circumvent a censorship, to express something that cannot be expressed in a serious manner for one reason or another.

A similar condition seems to be nowadays provided by the Internet. There, as in anonymous (or pseudonymous) leaflets thrown on the street, things said have an intermediate quality of an “open secret”; they are neither totally private, nor totally public, which allows room for maneuvering and experimentation. Things can be said there tentatively, without a signature, without anybody in particular taking full responsibility for them –with the same fluidity as in jokes, one would be tempted to say.

Maybe this is one reason why the locus where a great deal of the discursive practices through which ponticity is being performed is the cyberspace.

If we look at some of these expressions, we would find maybe not so radical, but equally positive references to a rebellious spirit, to non-conformity. These expressions have the same fluidity and oscillation between belonging and not belonging, in and out, back and forth.

One of the most common Pontic dances is called ombropìs. This unusual composite is made from the words “ombròs” [in standard Modern Greek embròs = in front of, forwards] and “opìsô” [behind, backwards]. No conjunction is used; we have here one single word with no adhesive substance between its two parts. So the name of this dance means not exactly “back and forth”, but, better, “forthback”. It combines the two opposites not in the sense of an alternation or a temporal sequence, but in simultaneity.

This feeling of oscillation and tentativeness is conveyed by almost all online expressions of the Pontian particularity.

One of the most prolific sites where such experimentation is being deployed for several years now, is a blog called “Pòntos kai aristerà” [Pontos and the Left]. In their presentation text[8], the authors explain their title choice with the following words:

The Pontos constitutes an underground process, which is subversive –hence leftist- for our images up to now. Leftist not in the traditional manner of modern Greeks, but in the old, the primordial sense of the word: the sense of resistance, of dissidence, of rebellion vis a vis the official norms of power (emphases in the original).

What is remarkable about this definition is that it is totally de-territorialized, in the most literal sense: according to it, the Pontos is not a toponym, does not designate any geographical space, nor its memory; it is only an immaterial process [διαδικασία].

Translating this text is quite tricky, as the original text in (standard) Greek conveys a feeling of awkwardness; its style is unstable, as happens when the person writing does not fully master the language, and/ or does not want to spell out everything s/he has in mind, preferring to speak with allusions and hints. Nevertheless, or maybe precisely for this reason, it is clear that the text conveys this “ombropis” feeling: the Pontians “sort of” conform to hellenicity, but at the same time they subvert it; even their subversion is not similar to the Modern Greek way of subverting. Their dissidence is dissident itself. But this novelty is not really new; it is a linkage to something old, and, indeed, “primordial” [arkhégono].

What is this “primordiality”? One legitimate interpretation can be, I think, the following: it is the memory of the times before the [Greek] [nation] state. “Pontos” is the name for a rebellion that is not intended to abolish a state or a government in place in order to replace it with another, better society to come; it is about exodus, withdrawal from the “norms of power”.

One thousand Parkhàrs

These, and other, “forthback” formulations are to my view a clear indication that there is also another source for the resistance of Pontic populations to the pressure for national homogenisation. Apart from their nostalgia for another state that (almost) existed in the past, and their desire to create an imaginary substitute for it, the tendency of the Pontians not to (fully) belong (any more) to the Greek nation-state is an expression of a desire for the non-state, for escaping the state as such (Gavriilidis 2015b).

This may sound as a paradox, as contradictory, but I believe both of these antithetical tendencies coexist in the same practices and performances of Pontic identity. Things that, for the binary modernist logic of nation-states, would be considered as incompatible, are not necessarily so for the non-statist logic of (some of) their subjects.

(Besides, desiring a state that never existed is not after all such a far cry from desiring no state).

The ombropìs effect is something that pops up every time we engage not only with music and dances, but with all the neo-Pontic performances at large. I propose that these could usefully be conceived as constituting one “fairly comprehensive cultural portfolio of techniques for evading state incorporation” (Scott 329). They display the same “remarkable plasticity and adaptability” developed by “marginal peoples [who] have, for the most part, long histories of defeat and flight and have faced a world of powerful states whose policies they had little chance of shaping” (314) and “had to thread their way through shifting and dangerous constellations of powers in which they have largely been pawns” (ibid.). Accordingly, I believe that the insistence of Pontic populations in Greece on their quintessential perennial Hellenicity is a strategic essentialism “permitting them to reinvent themselves” (Scott 314) and keep the state at a distance.

If we look at the «linguistic politics» around the comic book translations, the unusual stylistic choices and the constant will to diverge from norms, we will realize that these can be usefully read as constituting as many techniques of evasion. When one identifies oneself in a way that is different from, and incomprehensible to, the standard form at use in the population registers, what else is this if not a way of becoming non-transparent to the state and its clerks, if not a becoming imperceptible (Papadopoulos et al. 2008: 82, following Deleuze and Guattari).

In this sense, I believe the claim for a Pontic genocide, and the phenomenon of the revival of ponticity more generally, is a goldmine for the social sciences. In particular, anthropologists seem to be better equipped to conceptualise such phenomena. In my research in Greek (Gavriilidis 2014) I tried to build on Michael Herzfeld’s analyses, and more particularly on two specific notions, social poetics and cultural intimacy, that he developed while doing fieldwork in Crete – incidentally, another mountainous area, actually an island, where an analogous unwillingness and ambivalence is manifested as regards incorporation to the Greek state. An additional source, and an equally useful reading lens, would be to draw from the analyses of James C. Scott, another anthropologist who has never dealt with this zone of the world; instead, he focused on the opposite side of the continent: the Southeast rather than the Southwest Asia. Nevertheless, the case of the Pontians could be considered as a sign that many of his remarks are valid in other parts of the world as well. Notably the following, which I will quote at length:

Ethnic and “tribal” identity, in the nineteenth century and much of the twentieth, has been associated with nationalism and the aspiration, often thwarted, to statehood. And today, the utter institutional hegemony of the nation-state as a political unit has encouraged many ethnic groups in Zomia to aspire to their own nation-statehood. But what is novel and noteworthy for most of this long history in the hills is that ethnic and tribal identities have been put to the service not merely of autonomy but of statelessness. The paradox of “antistate nationalism”, if it might be called that, is typically overlooked. But it must have been a very common, perhaps the most common, basis for identity until, say, the nineteenth century, when, for the first time, a life outside the state came to seem hopelessly utopian. E. J. Hobsbawm, in his perceptive study of nationalism, took note of these important exceptions: “One might even argue that the peoples with the most powerful and lasting sense of what might be called ‘tribal’ ethnicity not merely resisted the imposition of the modern state, national or otherwise, but very commonly any state: as witness the Pushtun-speakers in and around Afghanistan, the pre-1745 Scots highlanders, the Atlas Berbers, and others who will come readily to mind (Scott 2009:244).

I added the emphasis on the expression “antistate nationalism”, for obvious reasons: the “social poetics” of Pontians around the memory of their would-be state at the Black Sea, and its imaginary substitute in Macedonia, can be considered precisely as an interesting and inventive sample of such nationalism.

But there is also another, more concrete impressive analogy with the situation of the Southeast Asian peoples. The latter’s “state evasion and state prevention”, according to Scott, has a very insistent geographic (or geo-political) dimension: it is always linked to the hills. The privilege space for power, from the proto-states to the colonial and post-colonial ones, has consistently been the plains. For anybody wanting to escape power, on the other hand, the handiest solution was to take to the hills, to be at a height.

In relation to these hills and their geo-cultural and political function, Scott, following Willem van Schendel, has adopted the generic term «Zomia» and argued in favour of the creation of what he calls «Zomia studies» (for a more detailed explanation of this term and its use see Scott 2009: xiv).

Within the Pontian “cultural intimacy”, there is one term/ notion that seems to be invested with particular and almost mystical importance and signification, not always easy to perceive and to explain, but in some ways analogous to the importance of the «hills» in Zomia. This is the parkhàr.

This word features in several traditional songs, (including the emblematic I kòr exéven so parkhàr = The young girl came out on the p.), and is also used as a basis for family names (Parkharìdis is a typical Pontian name).

The most obvious, literal solution to translate the parkhàr is plateau. The linguistic choice opens by itself the way for a parallel with Deleuze and Guattari’s famous A Thousand Plateaus.

The analogy is not limited to the terminological choice.

The importance of this notion was noticed quite early, form the first moment when learned people from Northwest Europe started studying the Pontos, its history and its physical and human geography with a scientific eye –with an anthropologist’s eye, as we would say today. One of the first such scholars of the time was no less than the German (born in Tyrol) historian Jakob Philipp Fallmerayer, who later became (in)famous in Greece for reasons not related to his Pontic studies.

In his History of the Trebizond Empire, published in 1827, Fallmerayer (who, in the respective entry of the German Wikipedia, is described as an «Orientalist») attached an edition of Mikhaìl Panaretos’s chronicle, annotated by him. Probably the lengthiest footnote added by the German “orientalist” concerns one (of four) occurrence of a strange term in Panaretos’s text: Παρχάρις. The phrase reads: ἀπῆλθε το φωσάτον ἡμῶν εἰς τόν Παρχάριν καί κουρσεύσαντες τούς Ἀμιτιώτας ἐπῆραν κοῦρσα πολλά [our troops withdrew/ left to the Parkhàris, looted the Amitiotes and took a large loot].

Fallmerayer is not quite sure what to make out of this term. Here is (part of) his footnote:

The word Παρχάρις [Parcharis] is new in Byzantine literature and is attested three or four times in Panaretos’s Chronicle, always as masculine and as paroxytonon [with the accent on the penultimate syllable; Greek in the original]. From the narration, it is clear that Parcharis is not a toponym, nor does it specify any particular region, but indicates a certain texture of the soil which was common in several parts of the imperial territory. (…)

The poor and ignorant population in today’s Trebizond does not understand the word ὁ Παρχάρις any more; but after asking for a long time, I was informed that the grassy, still inhabited and partly cultivated, but completely treeless alpine routes, which regularly appear above the always green forest zone of Colchis, covering all of its length and leading up to the sad, icecold plateaus of Upper Armenia, which the Turkish population calls رلرياج tschayerler, that is meadows, still today are called in the language of the Christian inhabitants Parcharitza[9].

The fact that the German scholar is lead, in this unusually long and convoluted period-paragraph, to adopt an almost «ombropìs» style himself, having recourse to three different languages and three different scripts to write them, in order to give his reader a somehow approximate notion of what the Parkhàr is, already points to a non-translatability, a discrepancy of the respective codes. The Parkhàr(is) is normally masculine, but may also be neutral or feminine (as implied by the last version ending in –itza); it is not a name place, but denotes a «texture of the terrain» (Terrainsbeschaffenheit); it is generally cultivated, but sometimes not; partly inhabited and partly not; it is above a certain height and runs through several countries. The Christian population «does not understand» this word, but still uses it. (This “still” was written for 1827, but continues to be valid in 2015). Fallmerayer himself is not even able to tell with certainty how many times it appears in the Chronicle, and gives two alternative values –three or four.

The Parkhàr/-is/-itza is where girls come out, but also where the Emperor’s troops go to face the nomadic war machine of the Turkic tribes –and, in order to face them, they adopt and imitate their ways: they withdraw [ὰπέρχονται] and loot villages[10]. It was also the place where bandits and/ or guerillas ran for refuge under the Ottoman Empire. It seems to be a name for what escapes any classification or qualification –what escapes tout court, without qualification; a name for the escape route itself, or for the place where escape routes may be traced and pursued.

One of these days, we should positively institute the field of the Parkhàr studies.

This could be a parody of a study field, but parodies are serious in their own way.

Conclusion: state prevention after the state

On the basis of what preceded, I conclude that the deployment of a specific Pontic subjectivity, and its recent transformations from the late 80s on, should not be seen as an “Ottoman remnant”; they do not constitute a survival of some pre-modern past doomed to fade out sooner or later through “historical progress”. Although such deployment is often formulated in the idiom of nostalgia, it does not (only) concern a longing for a return to some other time or space; it is, to a large extent, a performance that aims to –or in any case results in- a differentiation, an escape from the classifications the nation-state requires.

If this is so, it should lead to an extension of Scott’s basic idea: his basic insight seems to be useful not only for the area where he applied it on, namely Southeast Asia, but also elsewhere: Southwest Asia –and/ or Southeast Europe– as well.

But, apart from the spatial transposition, there seems to be ground for a temporal extension as well.

Indeed, this extension would run counter to Scott’s own “emphatic assertion” (p. xii) that what he has to say “makes little sense for the period following the Second World War”.

Since 1945, and in some cases before then, the power of the state to deploy distance-demolishing technologies —railroads, all-weather roads, telephone, telegraph, airpower, helicopters, and now information technology— so changed the strategic balance of power between self-governing peoples and nation-states, so diminished the friction of terrain, that my analysis largely ceases to be useful (ibid).

The case of the Pontian social poetics show, to my view, that this disclaimer was perhaps too hasty, or too modest: the examples of experimentation with writing, typography and the electronic medium imply that state evasion techniques may still be, and are, in use also after the nation-state has imposed itself, within it. People still can, under certain circumstances, constitute “tribes” and exert the art of not being governed not only in spite of the universal imposition and domination of communication technologies, but even through them –by appropriating and using them. Only, this time they do so not by preserving (geographical) zones of no statehood or nationality, but by producing virtual parhkàrs, tribes, and inter-tribal solidarity; by treating the Internet as one big immaterial “hill zone”; by hijacking the discourses and means mobilized by the state, both analogical and electronic, invest them with their own desires, the desires of an “anti-state nationalism”, and turn them against the statist purposes. A very useful way to achieve that is by creating situations of multiple statehoods or nationalities, of more than one –albeit of one and a half, situations of double domination by a real state plus another, imaginary/ ghost state. This can equally disrupt or sabotage sovereignty, because sovereignty can only be unique.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari (1987): A Thousand Plateaus. Capitalism and Schizophrenia, translation and foreword by Brian Massumi, Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press

Herzfeld, Michael (2004): Cultural Intimacy: Social Poetics in the Nation-State, New York and London: Routledge

Gavriilidis, Akis (2014): Emeìs oi époikoi. O nomadismòs tôn onomàtôn kai to psevdokràtos tou Pòndou [We settlers. The nomadism of names and the pseudo-state of Pontus], Yànnina: Isnafi

– (2015a): “On the Second Life of Institutions: The Ghost-State of Pontus in Macedonia”, in: Jim Hlavac & Victor Friedman (eds.), On Macedonian Matters: from the Partition and Annexation of Macedonia in 1913 to the Present, Munich: Kubon & Sagner, pp. 87-102

– (2015b): «The desire for the non-state: De-territorialization as an alternative lens to read late and post-Ottoman becomings», paper presented at the Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari: Refrains of Freedom Conference, Athens 2015, possibly to be published in the proceedings of the conference in 2016

Kosofsky Sedgwick, Eve (1990): Epistemology of the Closet, Oakland: University of California Press

Mazower, M. (2001): «The G-Word», London Review of Books, Vol. 23 No. 3, 8 February 2001.

Moro, Marie Rose (1998): Psychothérapie transculturelle des enfants de migrants, Paris: Dunod

Papadopoulos, Dimitris, Niamh Stephenson and Vassilis Tsianos (2008): Escape Routes. Control and Subversion in the Twenty-first Century, London/ Ann Arbor: Pluto Press

Sakai, Naoki (2006): «Translation», Theory, Culture & Society t. 23 (2–3)

– (2013): «The Microphysics of Comparison. Towards the Dislocation of the West», http://eipcp.net/transversal/0613/sakai1/en

Savvidis, A.G.K. (2009): Ιστορία της αυτοκρατορίας των Μεγάλων Κομνηνών της Τραπεζούντας (1204-1461) [History of the empire of the Grand Komnenoi of Trebizond (1204-1461)], Thessaloniki: Kyriakidis Bros

Searle, J.R. (1969): Speech Acts, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Scott, James C. (2009): The Art of Not Being Governed. An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia, Yale University Press, New Haven & London

Uderzo, A. 2003: Σπαθία και τραντάφυλλα, Σα ποντιακά έκλωσεν ατο τοι Σαββάντων ο Γέργον [Swords and Roses, translated into Pontian by Savvàndôn Yérgon], Athens: Μαμουθκομιξ.

[1] For the definition of “perlocutionary acts”, see Searle 1969: 25.

[2] In connection to the nation-state ambition mentioned in the introduction, we should bear in mind a well-known “professional joke” known to all linguists, according to which “language is a dialect with an army and a navy”.

[3] This absolute formulation needs some qualifying: there are persons, in Turkey and possibly in Russia or other former Soviet republics, who speak –or are familiar with- (some version of) Romeyka/ Pontic. But most, if not all, of them cannot read the Greek alphabet, and in any case these translations were certainly not made with them in mind.

[4] From this point of view, the Pontic version is not unique; since long, Astérix and other similar comics are being translated in several dialects and/or aspiring «languages without a state», such as Basque, Occitan, and Cretan in Greece.

[5] See more details about all this in Gavriilidis (2014), especially 237-249.

[6] Concerning the construction of this feeling of common belonging, it is very telling that the possessive pronoun in its Pontic version, the same term that we already saw being used in the small arbitrary addition to the Astérix map legend, i.e. “temeteron” [=one of our own], is widely used by Pontians, but also by non-Pontian Greeks in a slightly ironic way, to connote the capacity of being a Pontian.

[7] In some versions, appearing mostly in private publications, a third genocide is added: the one of the Assyrians (or «the Christians of Anatolia»). This however did not find its way in the legal texts.

[8] https://pontosandaristera.wordpress.com/2007/08/03/poioi-kai-giati/

[9] Panaretos’s Chronicle, as edited by Fallmerayer and published as an appendix in his Geschichte des Kaiserthums von Trapezunt, Munich 1827, was reprinted in Savvidis (2009). Τhis particular footnote appears on p. 299. My translation from the German.

[10] The word κοῦρσα used in this excerpt is adapted Greek plural for the Latin cursus (plunder), whence also the verb κουρσεύω, still currently in use in Modern Greek, and the noun κουρσάρος, an adaptation of the Medieval Latin cursārius, Eng. corsair (a pirate put in the service of an empire or state) and its counterparts in most European languages.